Tuesday 24 March 2015

Saint Patrick, Father of the Irish Nation

Saint Patrick was the father of this nation. Seeing how God had blessed his work, in the humble and simple yet attractive words of "his Confession before he should die," he wrote with the love and tenderness of a father about "the children that he had begotten" in the Christian faith. And ever since, the Irish people have loved and revered him as their father, the father of their nation.

Eoin Mac Neill, 'The Fifteenth Centenary of Saint Patrick, A Suggested Form of Commemoration' in Studies, An Irish Quarterly Review, Volume 13, no. 50 (June, 1924), 180.

Content Copyright © Trias Thaumaturga 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Monday 23 March 2015

Saint Patrick's Return to Slemish

Yesterday we looked at the account of Saint Patrick's enforced sojourn on the County Antrim mountain of Slemish by the American writer Paul Gallico. Today we are going to continue with this theme by looking at the same author's account of Saint Patrick's return to Slemish. This episode does not form part of Saint Patrick's own writings but is found in the Lives of the saint by later hagiographers. Modern scholarship doubts its historicity and despite Gallico's confidence that Slemish was 'richer in the presence and tradition of Patrick than almost any other spot in Ireland', some modern scholars are unconvinced that our national patron ever spent time here at all. The question of the geographical extent of Saint Patrick's mission, like so many other aspects of his life and career, remains open.

It was on, in and about Slemish and Skerry that Patrick acquired the practical education that in later years fitted him particularly for his mission to the pagan Irish. For it was here he learned the language, beliefs, customs, politics, laws and organisation. He became acquainted with their culture, characteristics, poetry, government, their strength and their weaknesses, and it was in these formative years that he learned to deal with the Irish.

It was on the approaches to Skerry likewise, and within sight of the Slemish of so many painful as well as sweet memories, that Patrick in later life upon his return to Ireland experienced a deep human tragedy and an affecting rejection, if there is more than the usual single kernel of truth in the legend connected with that return.

It is told that shortly after his landing in Ireland, in the vicinity of Strangford Lough and what is now Downpatrick, the Saint journeyed north to pay a visit to Miliucc, his old master, with a twofold purpose, both of which were characteristic of Patrick. He wished to pay off his debt to Miliucc in money, for Patrick never questioned slavery as an institution or a way of life in his times, and, when he had made his escape, he was well aware that he was robbing his master of a valuable piece of property which he had purchased at full price. It was this price that Patrick would have been eager to restore.

And then he desired to make one who by then must have been an old man his convert and rescue his soul before his death. However hard a lord Miliucc might have been, Patrick felt affection for him. The years that had intervened would have softened the memories of harshness, and left him with the same eagerness and excitement to see this man once again, as we are thrilled and excited over the prospect of returning to our old school after a long absence to hob-nob generously with the stern schoolmaster whom we once feared and perhaps even hated.

But Miliucc, according to the legend, was stubborn, hard-headed and intransigent. For reasons of his own he did not wish to face his former slave now returned as a dignitary of a new religion. It would not have been a guilty conscience, since no one felt guilty about slavery in those time, for there was no place or country in the world where it did not exist. Perhaps he was afraid that Patrick would convert him.

His reaction was drastic. According to the story he shut himself up in his Dun with all his treasure and personal belongings, kindled a fire and immolated himself.

Paul Gallico, The Steadfast Man - A Life of Saint Patrick, (London, 1958), 170-171.

Content Copyright © Trias Thaumaturga 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Sunday 22 March 2015

Saint Patrick and Slemish

Mount Slemish, Sliabh Miss, is located in the valley of the Braid in Antrim, in northern Ireland. This was the ancient Ulidia then divided into Dal-riada to the north and Dalaradia to the south, and Mount Miss as it was then called, Sliabh or Slieve being the Gaelic for 'Mount' was in northern Dal-riada...

The fore-hill of Slemish, which, when viewed from the side, is seen to be a part of it, is known as Skerry, and here was located the dun or fortress house of the Pictish chieftain Miliucc, the master to whom Patrick was sold as a slave. Slemish itself rises 1,437 feet from a barren and desolate moor. It is treeless as are all of the mountains of Ireland above a thousand feet. Yet there are green patches to relieve the mottled grey rock that reach almost to the top where from the north the outline of the formation known as Patrick's Chair may be seen. Field-glasses resolve the moving white dots upon these green patches into sheep grazing there, the descendants of the animals that Patrick herded there, perhaps....

It was on the harsh, chill, wind- and rain-swept crest of Slemish that Patrick found the presence, comfort and the love of God, just as it was to the still higher peak of Aigli that he went to communicate with Him.

The mountain has always been man's stairway to God. Stand upon the summit of Mount Canaan between Galilee and the sea at night when the heavens curve downwards and the stars may be touched ... and the feeling of the Presence is unmistakeable.

It was on the slopes of Slemish that God first spoke to Patrick.

Here it was that for six years, from the age of sixteen to twenty-two, Patrick the slave tended the swine of Miliucc in the forests where they fed on acorns or rooted beneath the moss. At other times, he took the sheep to the high pastures atop of Slemish and herded them in wind and weather.

Look upon Slemish today and you can grasp something of the ordeal of a lonely boy snatched from loving and indulgent parents and a life of ease and luxury to the rigours of slavery, exile and abuse. For Slemish is in itself a lonely mountain standing in isolation in the plain like an island rising from the ocean. Its brow caught the brunt of the storms whirling in from the sea, the driving rains and snows, the cold mists and fogs, with not so much as a sapling beneath which to shelter.

It was during these six years and upon this mountain that the character of Patrick was formed. The iron went into his body as the Spirit entered into his soul. Here he acquired the hardy frame and physical endurance that were to see him through his missionary years in Ireland. Here he suffered spiritually and bodily until he could suffer no more, until there was no more that life could do to him that it had not done.

... Here too he came to that faith in God, that belief in His concern for him, and that love for Him, that were to become his guide and support to the end of his days.

You cannot see the place where the infant Patrick first saw the light of day, for no one can point out the spot or name it, and no two scholars agree where it might have been, but when you gaze upon Slemish you are in the presence of the site where Patrick the man and the Apostle of Ireland was born out of the chrysalis of Patrick, the indolent, sinful boy.

... The slopes and vicinity of Slemish, then, are richer in the presence and tradition of Patrick than almost any other spot in Ireland. Yet there is no shrine there, marker or tablet, not even one of those appalling white statues of studied anachronism supposed to represent this remarkable man.

Paul Gallico, The Steadfast Man - A Life of Saint Patrick, (London, 1958), 166-169, 172.

Content Copyright © Trias Thaumaturga 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Saturday 21 March 2015

The Mountains of Patrick

There are two mountains in Ireland that played an important part in the life of St Patrick, two isolated peaks, strangely and more than coincidentally similar in shape, not connected with any chain, one on the east coast, the other on the west, rising starkly from the plain. They are today exactly as they were when Patrick knew them. On the slopes of one, Mount Slemish, Patrick the boy slave once herded sheep and swine for a master. On the peak of the other, Mount Aigli, now Croagh Patrick, he may well have retired to meditate.

It is a curious feature of both these mountains when approached from the south that each resembles a cone or pyramid, each has a small extension or fore-peak, and each, when one approaches more closely and finds oneself alongside it, changes its aspect to a kind of round, hump-backed mountain, something like an inverted bowl, though Croagh Patrick remains more pointed at the top than Slemish, and is slightly more than a thousand feet higher.

... The Mountains of Miss and Aigli have looked upon the labours of Patrick and, too, upon Patrick himself, the steadfast man.

Paul Gallico, The Steadfast Man - A Life of Saint Patrick, (London, 1958), 165-166, 176.

Content Copyright © Trias Thaumaturga 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Content Copyright © Trias Thaumaturga 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Friday 20 March 2015

Saint Patrick, a Man in whom the Spirit Prayed

People may say — " He is almost a myth — who knows anything about him." His birthplace, his grave, are uncertain. Old writers have woven a tissue of doubtful miracles for his fame, and who can say what the real man was.'' " But a man lives on in his own words, and in nothing material is he so immortal as in his letters.

To know Patrick you must read his Confession, and his flaming, righteously angry letter to Coroticus. In the Confession we get the real man beyond any doubt, as we find St. Paul in his own Epistles.

You may be disappointed to find so few of the facts of his life in the Confession, but you find a man's spirit, hurt with the wounds given to him by distrust and harsh criticism from his friends. You find a man very humble about his failures, about his lack of scholarship, yet proud, with head held high, in his vocation and in his conscious honesty of purpose. You find, too, what we might forget in the man of endless business and determined fighting, the man of prayer.

There was the vision and the call, given in his own words: "We beseech thee, holy youth, to come and walk once more amongst us." " And on another night, whether within or beside me I know not, God knoweth, in the clearest words, which I heard but could not understand until the end of the prayer. He spoke out thus: 'He who laid down His life for thee. He it is who speaketh within thee.' And so I awoke full of joy. And once more I saw Him praying in me and He was as it were within my body; and I heard Him over me, that is over the interior man; and there strongly He prayed with groanings. And meanwhile I was astonished and marvelled and considered who it was who prayed within me; but at the end of the prayer He spoke out to the effect that He was the Spirit; and so I awoke and remembered the Apostle saying: 'The Spirit helpeth the infirmities of our prayer. For we know not what we should pray for as we ought, but the Spirit Himself asketh for us with unspeakable groanings which cannot be uttered in words.' "

This is the spirit of the man who spent forty days and nights on Croagh Patrick, striving for the salvation of his chosen country. The old legends of his bargain with the Almighty is like a mist on the mountain. This man in whom the Spirit prayed was a greater than his chroniclers could estimate.

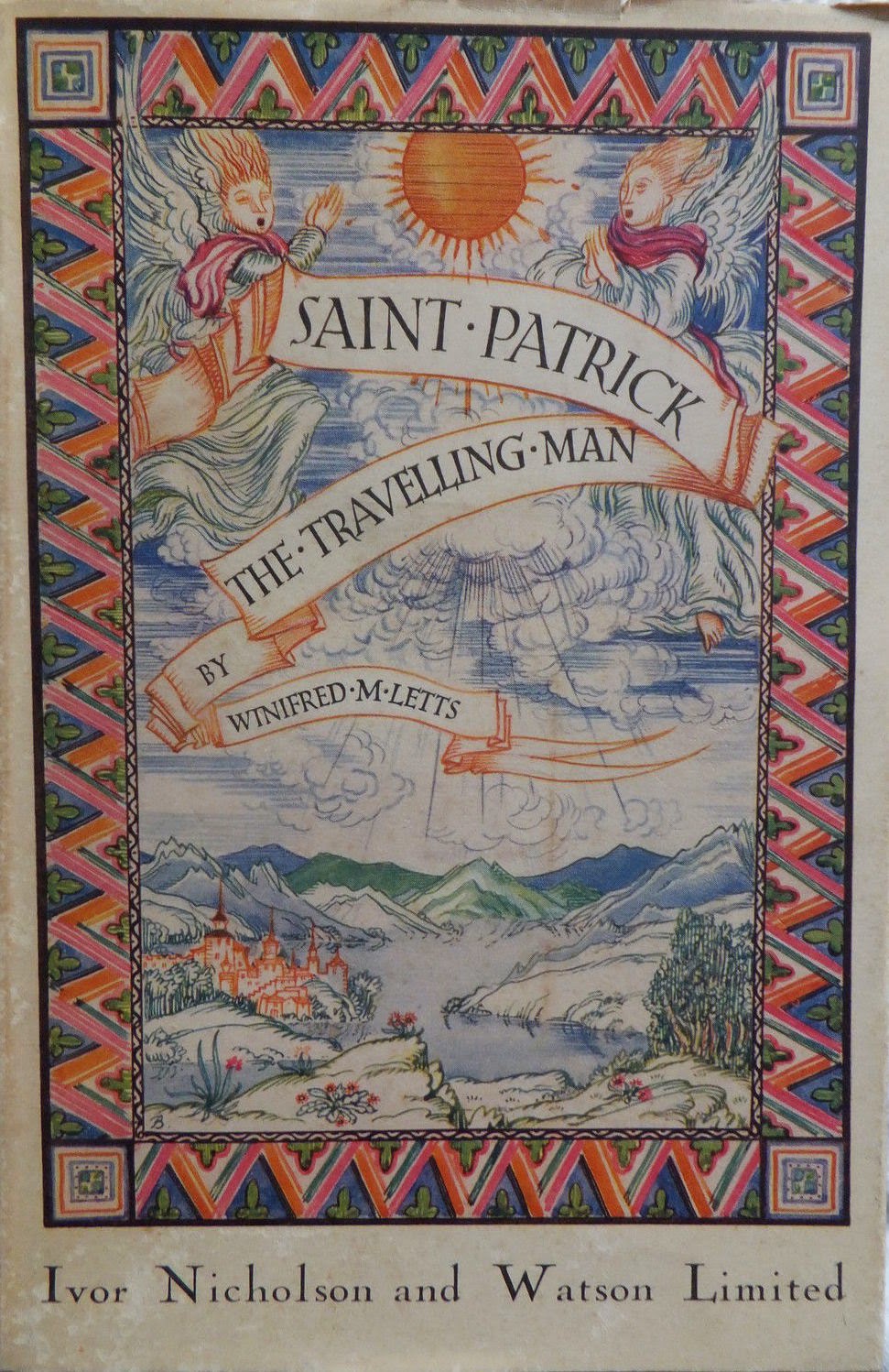

Winifred M. Letts, Saint Patrick, The Travelling Man (Edinburgh, 1932), 13-14.

Content Copyright © Trias Thaumaturga 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Content Copyright © Trias Thaumaturga 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Thursday 19 March 2015

Traces of Saint Patrick in County Antrim

|

| A 1936 cigarette card |

...Among the memories of my childhood's home on the Antrim coast, I can recall how often I walked the mountain road, higher and higher, until a well-known spot was reached where the great dome of Slemish began to appear above the other hills. On the other side of the valley of Glenarm was the site of the ancient church of Gleoir, founded by the apostle. That was where my mother's kin belonged. Nearer home, a path along the front of the cliffs that rise above the coast road led to Saint Patrick's Well. It was not right to pass the well without making a votive offering of some part of your belongings; the combined sentiments of reverence and thrift had brought about a uniformity of observance, and the well came to be commonly named the Pin Well. At the foot of Slemish is Baile Luig Phádraig, "the Hamlet of Patrick's Hollow" - there in my early memory lived the last native Irish-speaker in that district, who had the reputation of always saying his prayers in Irish - I think his name was Harry MacLoughin. On the further side of the Braid valley from Slemish is Skerry, Sciridh Phádraig, "Patrick's rocky hill." On the top of this hill there is a ruined church which the saint is recorded to have founded, and surrounded by a burial ground in which some of my kinsfolk had buried their dead from time immemorial. In this burial ground is a rock on which the angel Victor was supposed to have left his footprint - it was pointed out to me more than forty years ago. The legend was known to the author of "Fiacc's Hymn" more than a thousand years ago. He tells how the angel came to Patrick in his captivity: "Victor said to the slave that he should flee from Míliucc across the waves: he set his foot upon the flag, its trace remains, it does not fade."....

Eoin Mac Neill, 'The Fifteenth Centenary of Saint Patrick, A Suggested Form of Commemoration' in Studies, An Irish Quarterly Review, Volume 13, no. 50 (June, 1924), 181-182.

Content Copyright © Trias Thaumaturga 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Wednesday 18 March 2015

'Buez, or Life of Saint Patrick' - a Breton Mystery Play

Sometimes in my forays through the archives it seems that there are so many biographical accounts of our national patron that it is hard to distinguish between them. But in the article below we have something genuinely different, an analysis of a medieval mystery play featuring Saint Patrick. To make it even more interesting, the play is not of Irish origin but of Breton. The entire work is a curious mixture of events from Patrician writings and hagiography fused with later medieval traditions about Saint Patrick's Purgatory at Lough Derg, County Donegal. Saint Patrick's Purgatory exercised a fascination for medieval European writers and accounts of the wonders and torments to be experienced there appeared in a number of versions including Catalan and French. There are some obvious anachronisms in the play, for example, the parents of the fifth-century Saint Patrick are depicted as entering the Franciscan order. The most charming aspect of the play, apart from the flexible chronology, is the epilogue which the author of the paper has translated.

A LEGENDARY LIFE OF SAINT PATRICK.

BY JOSEPH DUNN, PH.D.

It was doubtless owing to the motive of connecting the

Apostle of Ireland with Armorica that at least three ancient lives of the saint

laid the scene of his capture by pirates in Brittany. According to later Breton traditions, St. Patrick was born

near Pont-Aven, in the garden land of Brittany, whose fame as the

"Millers' town " par excellence has given rise to the couplet

Pont-Aven, ville de renom,

Quatorze moulins, quinze maisons ;

a chapel is dedicated to him at Lannion, at the opposite

side of the peninsula, and, according to the popular almanacs, he is invoked

for the relief of the dead.

St. Patrick figures as one of the dramatis personae

in at least two Breton mystery plays. In the older, the "Life of St.

Nonne," mother St. David, which, by the way, is one of the earliest Breton

texts extant, dating from the fifteenth century, he plays a strange role. God

the Father despatches an angel to Patrick to tell him that, in obedience to a

design of Providence, he shall leave the place in which he is and that, in

thirty years, David will be born. Patrick demurs to this plan:

"What!" he exclaims, "I to fast for some one that will not be

born for thirty years, expose myself to dangers in foreign lands and go with bent-down

head like a blind man? What does God, the true King of the world, wish? I have

always served him as his liege-man the best I could, but, now that he intends

to exile me from this land, I will serve him no more." Again the angel is

despatched and, on the assurance that he will be made apostle of the island to

which he is to be sent and that no harm will happen to him, Patrick gives his

consent to go. He then hires a ship and sailors to take him to Ireland to

preach there the faith of Christ.

In the other mystery play, still inedited and existing in

only one manuscript copy dating from something more than a century ago, Patrick

is the chief personage. In fact, the title of the play is the "Buez, or

Life of St. Patrick, Archbishop of Ireland." Neither the name of the

author nor of the copyist of this curious piece is known, but this much is

sure, that it was composed by a young clerk, a native of one of the cantons of

Treguier, as the dialect in which the play is written makes clear. Although the

author had had some education, it was not enough to prevent him from falling

into all kinds of errors in history and chronology, in spite of the fact that

he had the assistance in its composition, as he himself tells us, of a

"Father of the order of St. Francis, a learned man and prudent, and full

of wisdom." But, after all, the poor poet is frank enough in confessing

that his work is "without study or style."

Like all the Breton mysteries, the "Life of St.

Patrick" is in verse, the favorite meter being the French Alexandrine ;

but occasionally other meters are employed, and the verses rhyme in pairs. It

is not uncommon to find whole phrases repeated in the course of the work, and

mere stop-gaps are found on every page. In a word, the style of the piece is as

mediocre and as prosaic as most of the Breton works of the same kind. Yet, in

spite of all that, it is valuable from the point of view of language, and for

the light it throws on the life at the time it was written, for, it may not be

out of place to remark, the authors of the Breton mystery plays represent the

characters of their dramas as contemporaries, no matter when or where they

lived. Consequently, we should be asking too much if we looked for historical

truth in these naive productions, whose primary purpose was to edify the

audience before whom they were to be given. Therein lay the greatest value of

the Breton theatre.

Long after the mystery plays had disappeared from the rest

of France, to give way to the comedy and drama, this mediaeval genre lived on

in Brittany and afforded the Breton peasantry their best diversion and their

only information, even if somewhat distorted, on sacred and profane history.

The author of a mystery did not bother himself much, and his auditors bothered

themselves even less, about the historicity of the subjects and characters of

the play. For this reason he chose, it made no difference whence, the subject,

taking care, however, to hit upon one that would draw and hold the people. The

author of the "Life of St. Patrick" excuses himself for not having

introduced farces and pleasantries into his play, which, he admits, would have

delighted the playgoers. And yet, he had not acted niggardly in this respect,

one would think, for he metamorphosed the druids or pagan priests of the cruel

king of Ireland who persecuted Patrick into devils, who speak big oaths and

thump and pummel each other to the great amusement of the audience.

There must have been a great many versions of this legendary

life of the Apostle of Ireland, of which the Breton Buez is but one. It will be

sufficient to mention here one in French, bearing close resemblances to the

play we are discussing, one in Spanish, due to the arch-priest Montalvan, and another in Spanish, based on this last, by the dramatist Calderon de la Barca.

There is every reason to believe that the Breton mystery was written to explain

the origin of the Purgatory of St. Patrick, and serve as introduction or

prelude to one of the numerous plays of that name. There could be no subject

that would appeal more to the imagination of the Breton of two hundred years or

more ago, as it would to the imagination of the Breton of to-day, than that

wonderful Purgatory which enjoyed such popularity towards the close of the Middle Ages, and

the marvelous adventures with which the converted soldier, Louis Eunius, met in

it.

The four versions mentioned do not agree on all points in

what they tell us of the life and works of Patrick. It will be worth while,

perhaps, to point out some of the most striking passages in which they agree or

disagree, taking the Breton text as the basis.

The first Prologue asks pardon of the audience for the

faults and rudeness of the work and the slips of the actors: "Excuse us, I

pray, if we make mistakes, and we will pray Jesus to pardon you, too." As

was the practice on such occasions, the players and audience kneel and join in

singing the Veni Creator, and thereafter, before entering upon the argument of

the play, the Prologue pays his respects to the clergy and nobility who are

present, requesting their attention : "On you, priests and nobles, depends

the attention of all present. Following your good example, they will give us

audience and all will remain silent."

Now, says the legend, in that part of Ireland that lies

opposite England and is near the sea is a small, sparsely peopled village

called Emothor or Emptor. This is Nemthur, where, according to the Old- Irish

Hymn by Fiacc of Sletty, one of the oldest Lives of Patrick, Patrick was born.

At a time that is not more definitely stated in the legend there lived in

that place a knight and, not far away, a lady whose name was Conchese, or

Conquesa, who is the Concess of the oldest Irish Lives. Both this young man and

woman had made vows of celibacy, but God the Father announced to them through

his angel Gabriel that their vows were not pleasing to him, for he had chosen

them for each other. The Breton play alone informs us that the knight was at

that time sixteen years of age and the lady fourteen. Moreover, his name was

Timandre, a name unknown to the other versions. From more reliable sources,

however, we know that his name was Calpurnius, that he was a Briton and a Roman

citizen, and that his home was at Bannaventa, which was probably in what is now

southwest Wales.

The Breton Buez differs further from all the other versions

in calling the maiden Mari Jana. She, says the Breton poet, was sister of St.

Germain (of Auxerre), but the others have it that she was sister of St. Martin

of Tours. In any case, they agree in affirming that she was of French blood,

and Calderon contents himself with informing us that Patrick, for he it is who

was afterwards their son, was born

De un caballero irlandes

Y de una dama francesa.

The proposals of marriage of Timandre and Mari Jana are

carried out with much formality in the presence of the young lady and her

brother, the count. Timandre is supported by his adviser, the vicar, who does

most of the parleying for his client. The next scene takes place in the church.

The vicar asks the names of the young couple :

" My name is Timandre, at your service ; in that name I

was baptized into the faith and into the Church. "

"And mine," answered his betrothed, "is Mari

Jana, also at your service."

The Vicar: "Well, Timandre, are you willing to take

this Mari Jana who is here present ?"

Timandre: "Yes."

" And you, Mari Jana, do you also promise to take for

your husband Sir Timandre ?"

" Yes."

The vicar then addresses them a short homily on the meaning

of the Sacrament of Matrimony, and, at the conclusion of the ceremony, the

entire company go to the wedding feast.

In general, the Breton author is better informed and more

precise than the other writers I have quoted. It was five years, he tells us,

before the prayers of this virtuous couple were answered; "a thing," he adds, "of rare occurrence in

that land." The visitation of the angels at the birth of the child, and

the scene of his baptism, take up considerable time in the action of the play,

for the questions of the priest and the responses of the page and governess,

who act as sponsors, are given in full, just as those of the priest and the

child's parents on the occasion of their marriage. At the command of the angel

Gabriel, the name Patrick is given to the boy. One might suppose, from the silence

of the Breton author on the subject, that Patrick was the only child of this

marriage; but we learn from the other accounts that he had three sisters (or

even five, according to a note in the Franciscan copy of Fiacc's Hymn in Honour

of St. Patrick) namely: Lupina, Ligrina, and Dorche - the two last are called Tygridia and Dorchea by

Montalvan of whom the first

mentioned remained single, but the others married, and the second had

twenty-three children, nephews of Patrick.

These popular versions agree in saying that Patrick's

parents ended their days in a cloister; and the Breton author, presumably to

flatter some local community and without regard to the violent wrenching of the

chronology, says that Timandre entered the order of St. Francis and that the

mother of Patrick became a religious of the order of St. Clare. They had left

the boy, a mere child, in the care and guardianship of the count, his mother's

brother, says the Breton author; but, say the others, it was to a lady, who according to the French

version was his aunt, to whom he was entrusted. In any case, he was afterwards

put to school with the faithful vicar, who, for a certain stipend, engaged to

teach him reading, writing, and the catechism, the boy having expressed his

preference for learning rather than for a martial career. He was only a lad of

six when he performed miracles: he restored sight to the eyes of a man who had

been blind from birth ; and he could not have been much older, ten, eleven, or

twelve years of age, according to the French version and Montalvan, when, by

his prayers, he caused a deluge, which had come from the melted snow and threathened to destroy all the land, to subside.

Meanwhile the devils have heard of the miraculous deeds of

the child, and of the spread of the faith which he preaches, and, filled with

alarm, they convene a council. As these scenes of deviltry are those in which

the Breton playwrights and actors made their master-stroke, and as the one

before us is typical of the class, it will, perhaps, be well to translate word

for word a portion of it. We can imagine the mirth of the spectators when some

well-known local figure was held up to ridicule. Lucifer summons the princes of hell "to stretch their

legs," and calls upon each to give an account of himself. "It's a

long time," he cries, "since any one has come to the fire," and

he gnashes his teeth with rage.

Beelzebub speaks : "Prince, here's a draper I've

brought down. I pretended to be a simpleton and he gave false measure. He

measured his laces and ribbons too short and then sold them at twice what they

were worth."

Asteroth speaks : " I've trapped an inn-keeper that

kept false accounts. He stole from his customers when their bellies were full,

put water in the wine and vinegar, sold for eighteen sous an article worth

fifteen, gave nine or ten eggs for a dozen, and charged five sous for an omelet

fried in a sauce of watery cider and dishwater."

Satan, to whom had been entrusted the surveillance of

Ireland, reports : "There is a brat there who does more harm than a dozen

of us. So I advise you to send some one else, if you wish, but I shan't go

there again." The upshot of the wrangle is that Asteroth proposes that

some one seize Patrick and denounce him to the emperor, and Beelzebub volunteers to

undertake the task, disguised as a labourer.

The French version is the only one of the four that gives

details of the well-known story of the capture of Patrick by pirates. The

Breton simply mentions that Patrick was only eight years old at the time ; but

the French legend, which is nearer the facts in the case, has it that he was

sixteen, and that his capture happened in this way : Patrick was walking along

the seashore with a few companions, reciting the psalms, when he was taken

prisoner and brought to the far end of the island, where he was sold to a

prince of that land. This was the "Emperor" before whom Beelzebub led

and accused Patrick ; but, because of the boy's tender age, he was punished by

being sent away to a solitary place to watch his master's sheep, which are

substituted for the herds of swine of the native versions.

Then follows a droll scene in the Breton Buez. Patrick is in

the wilderness in prayer. God the Father sends the angel Victor to comfort him.

But Victor, who, of course, is unknown to Patrick, first tries his patience :

"Good-day, young shepherd ;what is new? You are quite lost to the world in

this lonely place. Have done with your melancholy; enjoy yourself. I have

cards; let us play a game and dance the steps I have learned at the

academy."

Patrick protests that he knows no games, and, besides he has

no money.

" What sort of a man are you, anyway ?" exclaims

Victor.

" A man lively and gay is worth the woods full of such

bigots. Come, without ceremony, let us make ourselves at ease. Let us dance a

little without more ado."

Finally, since Patrick does not yield to the temptation, the

angel makes himself known.

The germ of the story of the conversion of the two daughters

of the High King Loegaire by Patrick, Ethne the White and Fedelm the Red, is

well known even in some of the earliest accounts of the saint's life, but the

Breton dramatist has taken the mere mention of the princesses in its source and made a story of his own out of their meeting with Patrick.

The older sister accosts Patrick: "Good day, shepherd. Come here. Tell me,

are you content in this place? Two young ladies have come to see you, having

heard that you are beautiful."

Patrick makes a move to escape their advances.

"Listen," he says,"I am not used to talk to young ladies. That

belongs to people like you, not to a poor unfortunate so poorly dressed as I

am."

He even loses his temper: "It would be better for you

to go home and not have them looking for you for dinner. Hurry to your

soup."

As might be expected, the young ladies are greatly mortified

at having their charms and blandishments so ruthlessly rebuffed, and they

threaten to report him to their father. But, it is hardly necessary to add,

they are finally converted to the doctrine professed by Patrick.

The following scene represents the emperor asleep. An angel

stands at his right side, at his left stands Lucifer, who says :"Courage,

courage, my son. Have no fear in the world. I will protect you when you are

oppressed."

The Angel: "What, do you believe in the idols?"

Asteroth :"It's a great pity if he doesn't believe in

them, old imbecile."

The Angel: "Alas, whoever does not believe will be

lost."

The Devil: "You lie in your face. In this way they will

be saved."

The Angel : "It will be a misfortune if they believe in

them."

Asteroth :" Away from here, or I will close your beak,

For he is ours, have no doubt in the world."

Patrick's life with the cruel emperor has become so

unendurable that the angel buys his release for 20,000 crowns, and the second act

concludes with another scene of devilry.

Lucifer :" Good- day, companions, I've come back to see

you. Don't be surprised if I'm late, for, without exaggeration, I've been

traveling all over the parishes of the diocese of Treguier. Well,

Asteroth, have you succeeded in putting Patrick under your

law?"

Asteroth: "All the devils together are no match for

him. I have tried hard enough to tempt him "

"The deuce. You're a fine fellow, when a little chap

causes you such embarrassment. If I were at his heels, I'd have him in the net

"

Asteroth : " All the nets in the whole of hell are not

enough, I tell you, old stinkard, to catch a man who is in the grace of God.

You fool yourself, if you think so."

Lucifer: "What, wretch! I'll teach you to speak

hereafter in more proper terms. There, take that on your side, old heedless

ingrate. One like you doesn't earn his bread."

The different versions do not agree as to what happened to

Patrick on the journey to France, which followed his release from the tyrant in

Ireland. Some of them say it was St. Martin at Tours, others that it was St.

Germain at Auxerre whom he visited, and by whom he was ordained to the

priesthood.

Having expressed a desire to visit "the house of

Monsieur St. Peter," he set out for Rome. On the way, he was inspired to

visit a hermit named Justus who, says the French version, lived on an island in

the Tyrrhenian sea, by which we know from reliable documents that the island of

Lerins is meant, or, according to the Breton mystery, in the heart of a great

forest which we may suppose was on the Alps or Apennines.

When Patrick came up to the hermitage he called to the

hermit: "Holy father, open your door to me, I pray you, for the night has

come and I do not know where to go."

"Who is it wishes to enter?" asked the hermit.

"I cannot give lodging in any way."

"I am a priest on my way to Rome, and I pray you to

support me this night."

" Tell me your name, and we will see. If you are that

Patrick, surely I will take you in."

For it had been revealed to Justus that Patrick would pass

that way, and he had received from heaven a sceptre or crosier which he was to

deliver to Patrick on his coming. One form of this story dates from as early as

the ninth century.

By confusion with his predecessor, Palladius, Patrick is

said to have arrived in Rome in the pontificate of Celestine I., who conferred

upon him the benefice and archbishopric of Ireland.

The Breton mystery brings us to the Eternal City, where we

find Patrick conversing with the Pontiff and the cardinals. On his return home,

Patrick crosses France and again visits his uncle, who provides him with

"chalice, missal, and ornaments," for, as he says, in the land to

which Patrick is about to go there are no furnishings.

Patrick, the legend continues, landed on the coast of

Leinster, where he remained some time, and then embarked for Ulster in the

northern part of the island, where Leogarius, who is the Loegaire of Irish

history, reigned. Now this king, whom the Breton mystery calls Garius, had

planned, at the instigation of the devils, to destroy the apostle, and at the

suggestion of Beelzebub, he sent his chief prince to the church where Patrick

was saying Mass, with a pistol in his hand to shoot him ; but, as he is about

to fire, a thunderbolt hurls him to the ground. This incident is also a

reworking of one of Patrick's adventures with the Druids told of in some of the

early accounts of his life, how the chief Druid tried to kill Patrick, but the

saint raised his hand and cursed him, and he fell dead, burned up before the

eyes of all. From here on, event follows event in quick succession. St. Brigit,

who, by the way, is associated with Patrick only in the more recent lives,

appears and announces to Patrick the secrets which God has to reveal to him. A

stage direction follows: Here a light will be made in the sky. One of the inhabitants of Ireland cries

out: "Look, look, in the air, a great light full of brightness. I dare not

venture ; I will wait no longer to understand it. I am going to call people. I find

here a miracle." (Recalls at the door): "James, James. Come out

quickly. I am greatly perplexed at what I see. Look, in the air is a light like

a triumphant sun."

James in turn calls another : "William, come, my

friend. We are in fear here. There is a burning torch in the air above our

house." They fall on their knees. Brigit explains that it is a sign of the

joys prepared for Patrick in heaven.

God descends, a crosier in his hand, and leads Patrick to

the mouth of a cavern which serves as entrance to the miraculous Purgatory. God

promises Patrick that he will suffer no torment at the hour of death, for He

will come promptly with his angels to receive him.

Patrick speaks to the bystanders: "My vicar-general,

and you my people, the time has come that has been fixed to pay tribute to

Jesus, my Saviour. All that receive life must sometime die. It is not the fear

of death that is my greatest regret. My greatest sorrow is to leave behind the

Irish. I have always remembered them in my prayers, and in my sacrifices I

prayed for them. This much has been accomplished : I have obtained from Jesus,

our Messias, a new Purgatory, created in my name, and, because of me, it has

been privileged : Whoever passes twenty-four hours within it will efface

whatever offences he has committed in this world. Yonder it is, near the

valley. Come with me, we will visit it together."

A host of angels appear in the air singing Gloria in

excelsis Deo. Patrick, from within the Purgatory, addresses his farewell to

the pains and torments of the world, and the mystery concludes with another

scene of diablerie. Lucifer and Beelzebub had promised Satan, when we

saw them last, that they would act diligently on their mission, and not come

back emptyhanded. And now we find them condoling with each other, for they have

got no game, and they are afraid they will be struck and beaten. A happy

thought occurs to Beelzebub :" There is no chance of success in this land.

Come, let us go to Toulouse to get Louis Ennius. I saw him less than a week ago

living riotiously and quarrelsome and cuddling the pretty girls. Come, we

shan't have any trouble in taking him."

The vulgar versions of the life of St. Patrick reckon that

he lived to the age of 120 or even 130 or 132 years. According to the equally

unsubstantiated statements of the French version we are considering here, and

the Spanish of Montalvan, he was 113 years of age when he died. His burial

place was the city of Dun, or Dunio as the word stands in Montalvan, which

represents the historical Dun Lethglasse, which contests with Saul the honor of

containing the bones of the Irish apostle. The true year of his death was 461,

on the 17th of March. The legendary accounts disagree with this, and also with

each other. The French version offers the 20th of April, in the year 463; Montalvan the 16th of that month, in the year 493, and in the pontificate of

Pope Felix. These and other attempts at synchronizing are overlooked by the

Breton poet. It was sufficient for him to have produced a preface to and an explanation

of that other play which, in his eye, was of greater importance, and to the

performance of which he invites his audience to return on the morrow.

I cannot bring this short analysis of the " Buez or

Life of St. Patrick" to a better close than by giving a translation of the

Epilogue which followed it. It offers considerable information concerning the

spectators, the author, and the actors, and the obstacles and encouragement

which they might expect to meet with in the course of the play. The Epilogue

was the capital piece of a mystery and was technically known as the bouquet. It

must be remembered that these dramas were given on a temporary stage in the

open air and that it required several days to play one mystery entire. As the

reciter of the Epilogue, who was always the best actor of the troupe, declaimed

in flowery terms, the assistants passed among the audience taking up the

collection with which to defray the expenses of the production.

EPILOGUE.

Good people, generous people, people of every noble quality,

your favourable attention towards us to-day puts us under deep obligations, if

we had the capacity, to thank you from the centre of our hearts.

But, good people, relying on the patience which you have

continued to show to-day in our favour, I make bold to thank you, so far as I

am able, on the part of the actors.

Monsieur the pastor and all the priests have favoured us in

every way, and, in recompense, I thank them and the joy of Paradise I wish

them.

Then the nobles, the people of quality, who have shown us

every civility, in return we pray for them and I wish them the glory of

Paradise.

Next, the young clerics and the people of the pen, as well

as the citizens, I thank, and in turn I wish them, too, the glory of Paradise.

Besides, the heiresses, as many as are present, I thank

warmheartedly for having shown us perfect attention, and I ask for them joy in

heaven.

I thank you from my heart, young people, and I wish you a

thousand good fortunes, the wealth of the world, many children, and the

happiness of Paradise afterwards.

And I ask excuse of all, and once more I invite you all to

come to-morrow, if it be your pleasure. I hope that there will be three times

as many as there are to-day.

If we have displeased anybody to-day, we promise to satisfy

you to-morrow. We will spend our time and will take every pains that we may be

able to satisfy every one.

I do not doubt that there will be some hanger-on who, on the

way home or while eating his bowl full, will find a thorn to attach to each of

us ; I see mine already dragging behind me.

But those that are wise and well-intentioned will let them

have their say and invite them, if they know their business, to come to morrow

and to give a lesson.

The mystery which you will see is that of Louis Ennius,

which we will play, by the grace of Jesus, with the best persons who are able

to give it. Then, come all in bands, let no one remain at home.

Now, I have another thing to ask of you: Let every one

bring, without fail, a six-real piece; fifteen-sous piece, rolls of farthings,

and four-sous pieces will not be refused.

It is to help pay for our supper. And you, company, if you

wish to join us in drinking a drop, we will do it most willingly before we

leave.

Finally, company, this is your duty. But, those who may not

have a sou, come just the same and we will strive, all of us, to do our part

and satisfy you before you leave for home.

O glorious St. Patrick, you who are in heaven, be our

advocate now before God. With true heart, I make our request and that of all

who have come to hear us.

Our end and our design and inclination is to imitate you in

every way, in order that, by your example, we may overcome sin and be

victorious over our enemies.

Glorious St. Patrick, crowned with glory, cause us to imitate

your life in this world, that, having followed your example, we may share in

the glory and the joy.

In this way I began, in this way I end. I pray you, company,

excuse us. To-morrow, by the grace of God, we promise to do better. I am, with

true heart, your faithful servant.

Catholic World Volume 86 (1908), 461-472.

Content Copyright © Trias Thaumaturga 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Content Copyright © Trias Thaumaturga 2012-2015. All rights reserved.

Tuesday 17 March 2015

The Apostle of Ireland

On the feast of Saint Brigid we looked at an account of her life from a nineteenth-century author, John O'Kane Murray, who was writing for an Irish-American audience. We can now turn to the same writer's account of Saint Patrick and a marvellously stirring and romantic account it is too. This is the Victorian view of our national apostle in all its chauvinistic glory. Beanachtaí na Féile Pádraig oraibh!

THE APOSTLE OF IRELAND.

THE APOSTLE OF IRELAND.

DIED A.D. 465.

"All praise to St. Patrick, who brought to our mountains

The gift of God's faith, the sweet light of His love;

All praise to the shepherd who showed us the fountains

That rise in the heart of the Saviour above!

"There is not a Saint in the bright courts of heaven

More faithful than he to the land of his choice;

"There is not a Saint in the bright courts of heaven

More faithful than he to the land of his choice;

Oh! well may the nation to whom he was given

In the feast of their sire and Apostle rejoice.

In glory above,

True to his love,

He keeps the false faith from his children away —

The dark, false faith

Far worse than death."

— Faber.

ST. PATRICK, whose noble name [1] is revered in many lands, was born in the year 387, at Boulogne, in the north of France. [2] His father, Calphurnius, and his mother, Conchessa, a niece of St. Martin, Archbishop of Tours, were persons of rank and virtue. Conchessa, it is said, was noted for elegance of manners and beauty of person.

ST. PATRICK, whose noble name [1] is revered in many lands, was born in the year 387, at Boulogne, in the north of France. [2] His father, Calphurnius, and his mother, Conchessa, a niece of St. Martin, Archbishop of Tours, were persons of rank and virtue. Conchessa, it is said, was noted for elegance of manners and beauty of person.

The Saint's childhood was marked by many miraculous incidents. We can give but one. While

running about in a field one of his sisters slipped

and fell, striking her forehead against a sharp

stone. The girl was so stunned and severely

wounded that she seemed to be lifeless. Friends

anxiously gathered around, and her little brother

was soon on the scene. Patrick's surgery was

wonderful. He made the sign of the cross on

her blood-stained countenance, and instantly the

wound was healed. But the scar remained as a

sign to mark the spot where faith and holiness

had gained a victory.

The boy grew up in the bright way of virtue.

His merits far surpassed his years. In the words

of the venerable monk Jocelin, he went "forward

in the slippery paths of youth and held his feet

from falling. The garment that nature had woven

for him — unknown to stain — he preserved whole, living a virgin in mind and body. On the arrival

of the fit time he was sent from his parents to be

instructed in sacred learning.

" He applied his mind to the study of letters,

but chiefly to psalms and hymns and spiritual

songs, retaining them in his memory and continually singing them to the Lord; so that even from

the flower of his first youth he was daily wont to

sing devoutly unto God the whole psalter, and

from his most pure heart to pour forth many

prayers." [3]

But the day of trial was at hand. The future

Apostle of Erin was to be tested as gold in a furnace. When he had reached the age of sixteen,

the famous King Niall of the Nine Hostages,

monarch of Ireland, [4] swept along the coast of

France on a marauding expedition, and captured

the good youth with many of his countrymen.

Patrick was carried to the shores of Ireland, and sold as a slave to Milcho, a chief ruling over a portion of the county of Antrim.

The young captive was chiefly employed in

tending herds of sheep and swine on the mountains. It was a period of sore adversity. But

his soul rose above such lowly occupations and

held unbroken communion with Heaven. Thus,

in the heat of summer and the biting blasts of

winter, on the steep sides of Slieb-mish [5] or on

the lone hill-tops of Antrim, he recalled the sacred

presence of God, and made it a practice to say "a

hundred prayers by day and nearly as many more

at night." [6]

After Patrick had served Milcho for six years, he was one night favoured with a vision, as he relates in his " Confessions." "You fast well," said the voice. " You will soon go to your own country. The ship is ready." To Patrick this was welcome news.

"Then girding close his mantle, and grasping fast his wand,

He sought the open ocean through the by-ways of the land."

A ship, indeed, was about to sail, but he had much difficulty in obtaining a place on board. After a passage of three days he landed at Treguier, in Brittany. He was still, however, a long distance from his native place, and in making the journey he suffered much from hunger and fatigue. But he bravely triumphed over all obstacles — including the devil, who one night fell upon him like a huge stone — and reached home at the age of twenty-two, about the year 410.

The Saint now formed the resolution of devoting himself wholly to the service of God, and retired to the celebrated monastery of St. Martin at Tours, where he spent four years in study and prayer. After this he returned home for a time.

It was not long, however, before Patrick's future mission was shadowed forth by a vision. One night a dignified personage appeared to him, bearing many letters from Ireland. He handed the Saint one, on which was written: "THIS IS THE VOICE OF THE IRISH." While in the act of reading, he says, " I seemed to hear the voices of people from the wood of Fochut, [7] near the western sea, crying out with one accord: 'Holy youth, we implore thee to come and walk still amongst us.' Patrick's noble heart was touched. He "awoke, and could read no longer."

Saint and student that he was, Patrick now began to prepare himself with redoubled vigour for the vast work that lay before him. He placed himself under the guidance of St. Germain, the illustrious Bishop of Auxerre, who sent him to a famous seminary in the isle of Lerins, where he spent nine years in study and retirement. [8] It was here that he received the celebrated crosier called the Staff of Jesus, which he afterward carried with him in his apostolic visitations through Ireland. [9]

After Patrick had served Milcho for six years, he was one night favoured with a vision, as he relates in his " Confessions." "You fast well," said the voice. " You will soon go to your own country. The ship is ready." To Patrick this was welcome news.

"Then girding close his mantle, and grasping fast his wand,

He sought the open ocean through the by-ways of the land."

A ship, indeed, was about to sail, but he had much difficulty in obtaining a place on board. After a passage of three days he landed at Treguier, in Brittany. He was still, however, a long distance from his native place, and in making the journey he suffered much from hunger and fatigue. But he bravely triumphed over all obstacles — including the devil, who one night fell upon him like a huge stone — and reached home at the age of twenty-two, about the year 410.

The Saint now formed the resolution of devoting himself wholly to the service of God, and retired to the celebrated monastery of St. Martin at Tours, where he spent four years in study and prayer. After this he returned home for a time.

It was not long, however, before Patrick's future mission was shadowed forth by a vision. One night a dignified personage appeared to him, bearing many letters from Ireland. He handed the Saint one, on which was written: "THIS IS THE VOICE OF THE IRISH." While in the act of reading, he says, " I seemed to hear the voices of people from the wood of Fochut, [7] near the western sea, crying out with one accord: 'Holy youth, we implore thee to come and walk still amongst us.' Patrick's noble heart was touched. He "awoke, and could read no longer."

Saint and student that he was, Patrick now began to prepare himself with redoubled vigour for the vast work that lay before him. He placed himself under the guidance of St. Germain, the illustrious Bishop of Auxerre, who sent him to a famous seminary in the isle of Lerins, where he spent nine years in study and retirement. [8] It was here that he received the celebrated crosier called the Staff of Jesus, which he afterward carried with him in his apostolic visitations through Ireland. [9]

The learned and saintly priest returned to his patron, St. Germain, and passed several years in the work of the holy ministry and in combating heresy. In 430, however, St. Germain sent him to Rome with letters of introduction to the Holy Father, warmly recommending him as one in every way qualified for the great mission of converting the Irish people. A residence of six years in the country, a perfect knowledge of its language, customs, and inhabitants, and a life of study, innocence, and sanctity — these were the high testimonials which Patrick bore from the

Bishop of Auxerre to the Vicar of Christ.

Pope Celestine I. gave the Saint a kindly reception, and issued bulls authorizing his consecration as bishop. Receiving the apostolic benediction, he returned to France, and was there raised to the episcopal dignity. [10] The invitation, " Come, holy youth, and walk amongst us," rang ever in his ears. It armed his soul with energy. The new Bishop bade adieu to home and kindred, and set out for the labour of his life with twenty well-tried companions.

It is supposed that St. Patrick first landed on the coast of the county of Wicklow; but the hostility of the natives obliged him to re-embark, and he sailed northward toward the scenes of his former captivity. He finally cast anchor on the historic coast of Down, and, with all his companions, landed in the year 432 at the mouth of the little river Slaney, [11] which falls into Strangford Lough. The apostolic band had advanced but a short distance into the country when they encountered the servants of Dicho, lord of that district.

Taking the Saint and his followers for pirates, they grew alarmed and fled at their approach. The news soon reached the ears of Dicho, who hastily armed his retainers and sallied forth to meet the supposed enemy. [12] He was not long in learning, however, that the war which Patrick was about to wage was not one of swords and bucklers, but of peace and charity; and with true kindness and Irish hospitality, Dicho invited the apostle to his residence.

It was a golden opportunity. Nor did the Saint permit it to escape. He announced the bright truths of the Gospel. Dicho and all his household heard, believed, and were baptized. The Bishop celebrated Holy Mass in a barn, and the church which the good, kind-hearted chief erected on its site was afterwards known as Sabhall -Patrick, or Patrick's Barn. Thus Dicho was Patrick's first convert in Ireland. The glorious work was commenced. In that beautiful isle the cross was destined to triumph over paganism, and ever more to reign on its ruins.

The great missionary next set out to visit his old master, hoping to gain him over to the faith. But when Milcho heard of the Saint's approach, his hard heathen soul revolted at the idea that he might have to submit in some way to the doctrine of his former slave. The old man's rage and grief, it is related, induced him to commit suicide. " This son of perdition," says the ancient monk, Jocelin, "gathered together all his household effects and cast them into the fire, and then, throwing himself on the flames, he made himself a holocaust for the infernal demons." [14]

Pope Celestine I. gave the Saint a kindly reception, and issued bulls authorizing his consecration as bishop. Receiving the apostolic benediction, he returned to France, and was there raised to the episcopal dignity. [10] The invitation, " Come, holy youth, and walk amongst us," rang ever in his ears. It armed his soul with energy. The new Bishop bade adieu to home and kindred, and set out for the labour of his life with twenty well-tried companions.

It is supposed that St. Patrick first landed on the coast of the county of Wicklow; but the hostility of the natives obliged him to re-embark, and he sailed northward toward the scenes of his former captivity. He finally cast anchor on the historic coast of Down, and, with all his companions, landed in the year 432 at the mouth of the little river Slaney, [11] which falls into Strangford Lough. The apostolic band had advanced but a short distance into the country when they encountered the servants of Dicho, lord of that district.

Taking the Saint and his followers for pirates, they grew alarmed and fled at their approach. The news soon reached the ears of Dicho, who hastily armed his retainers and sallied forth to meet the supposed enemy. [12] He was not long in learning, however, that the war which Patrick was about to wage was not one of swords and bucklers, but of peace and charity; and with true kindness and Irish hospitality, Dicho invited the apostle to his residence.

It was a golden opportunity. Nor did the Saint permit it to escape. He announced the bright truths of the Gospel. Dicho and all his household heard, believed, and were baptized. The Bishop celebrated Holy Mass in a barn, and the church which the good, kind-hearted chief erected on its site was afterwards known as Sabhall -Patrick, or Patrick's Barn. Thus Dicho was Patrick's first convert in Ireland. The glorious work was commenced. In that beautiful isle the cross was destined to triumph over paganism, and ever more to reign on its ruins.

The great missionary next set out to visit his old master, hoping to gain him over to the faith. But when Milcho heard of the Saint's approach, his hard heathen soul revolted at the idea that he might have to submit in some way to the doctrine of his former slave. The old man's rage and grief, it is related, induced him to commit suicide. " This son of perdition," says the ancient monk, Jocelin, "gathered together all his household effects and cast them into the fire, and then, throwing himself on the flames, he made himself a holocaust for the infernal demons." [14]

At this time Laegrius, [15] supreme monarch of

Ireland, was holding an assembly or congress of

all the Druids, bards, and princes of the nation

in his palace at Tara. St. Patrick resolved to be

present at this great meeting of chiefs and wise

men, and to celebrate in its midst the festival of

Easter, which was now approaching.

He resolved with one bold stroke to paralyze the

efforts of the Druids by sapping the very centre

of their power. He resolved to plant the glorious

standard of the Cross on the far-famed Hill of

Tara, [16] the citadel of Ireland. Nor did he fail.

It was the eve of Easter when the Saint arrived at Slane [17] and pitched his tent. At the same hour the regal halls of Tara were filled with all the princes of the land. It was the feast of Baal-tien, or sun-worship; and the laws of the Druids ordained that no fire should be lighted in the whole country till the great fire flamed upon the royal Hill of Tara. It so happened, however, that Patrick's Paschal light was seen from the king's palace. The Druids were alarmed. [18] The monarch and his courtiers were indignant. The Apostle was ordered to appear before the assembly on the day following.

"Gleamed the sun-ray, soft and yellow,

On the gentle plains of Meath;

Spring's low breezes, fresh and mellow,

Through the woods scarce seemed to breathe;

And on Tara, proud and olden,

Circled round with radiance fair,

Decked in splendor bright and golden,

Sat the court of Laeghaire —

"Chieftains with the collar of glory

And the long hair flowing free;

Priest and Brehon, bent and hoary,

Soft-tongued Bard and Seanachie.

Silence filled the sunny ether,

Eager light in every eye,

As in banded rank together

Stranger forms approacheth nigh,

"Tall and stately — white beards flowing

In bright streaks adown the breast —

Cheeks with summer beauty glowing,

Eyes of thoughtful, holy rest;

And in front their saintly leader,

Patrick, walked with cross in hand,

Which from Arran to Ben Edar

Soon rose high above the land."

The Apostle preached before Laegrius and the great ones of Tara. " The sun which you behold," said he, " rises and sets by God's decree for our benefit ; but it shall never reign, nor shall its splendour be immortal. All who adore it shall miserably perish. But we adore the true Sun — Jesus Christ." [19]

The chief bard, Dubtach, was the first of the converts of Tara; and from that hour he consecrated his genius to Christianity. A few days after Conall, the king's brother, embraced the faith. Thus Irish genius and royalty began to bow to the Cross. The heathen Laegrius blindly persevered in his errors, but feared openly to oppose the holy Apostle. The scene at Tara recalls to mind the preaching of St. Paul before the assembled wisdom and learning of the Areopagus. A court magician named Lochu attempted to oppose St. Patrick. He mocked Christ, and declared that he himself was a god. The people were dazzled with his infamous tricks. The hardy impostor even promised to raise himself from the earth and ascend to the clouds, and before king and people he one day made the attempt. The Saint was present. " O Almighty God!'' he prayed, " destroy this blasphemer of thy holy Name, nor let him hinder those who now return, or may hereafter return, to Thee." The words were scarcely uttered when Lochu took a downward flight. The wretch fell at the Apostle's feet, dashed his head against a stone, and immediately expired.

After a short stay at various points, St. Patrick penetrated into Connaught. In the county of Cavan he overthrew the great idol called Crom-Cruach [20] and on its ruins erected a stately church. It was about this time that he baptized the two daughters of King Laegrius. The fair royal converts soon after received the veil at his hands.

The Apostle held his first synod in 435, near Elphin, during which he consecrated several bishops for the growing Church of Ireland. It was in the Lent of this year that he returned to Crtiach-Patrick, a mountain in Mayo, and spent forty days, praying, fasting, and beseeching heaven to make beautiful Erin an isle of saints.[ 21] The most glorious success everywhere attended his footsteps. The heavenly seed of truth fell on good ground, and produced more than a hundred-fold. Nor did miracles fail, from time to time, to come to the aid of the newly-announced doctrine. He reached Tirawley at a time when the seven sons of Amalgaidh were disputing over the succession to the crown of their deceased father. Great multitudes had gathered together. The Saint made his voice heard. An enraged magician rushed at him with murderous intentions; but, in the presence of all, a sudden flash of lightning smote the would-be assassin. It was a day of victory for the true faith. The seven quarrelling princes and over twelve thousand persons were converted on the spot, and baptized in the well of Aen-Adharrac. [22]

St. Patrick, after spending seven years in Connaught, [23] directed his course northward. He entered Ulster once more in 442. His progress through the historic counties of Donegal, Derry, Antrim, and others was one continued triumph. Princes and people alike heard, believed, and embraced the truth. Countless churches sprang up, new sees were established, and the Catholic religion placed on a deep, lasting foundation. The Apostle of Erin was a glorious architect, who did the work of God with matchless thoroughness.

" From faith's bright camp the demon fled,

The path to heaven was cleared;

Religion raised her beauteous head —

An Isle of Saints appeared."

The Apostle next journeyed into Leinster, and founded many churches. It is related that on reaching a hill distant about a mile from a little village, situated on the borders of a beautiful bay, he stopped, swept his eye over the calm waters and the picturesque landscape, and, raising his hand, gave the scene his benediction, saying: "This village, now so small, shall one day be renowned. It shall grow in wealth and dignity until it shall become the capital of a kingdom." It is now the city of Dublin.

In 445 St. Patrick passed to Munster, and proceeded at once to " Cashel of the Kings." Angus, who was then the royal ruler of Munster, went forth to meet the herald of the Gospel, and warmly invited him to his palace. This prince had already been instructed in the faith, and the day after the Bishop's arrival was fixed for his baptism. During the administration of the sacrament a very touching incident occurred. The Saint planted his crosier — the Staff of Jesus — firmly in the ground by his side; but before reaching it the sharp iron point pierced the king's foot and pinned it to the earth. The brave convert never winced, though the pain must have been intense. The holy ceremony was over before St. Patrick perceived the streams of blood, and he immediately expressed his deep sorrow for causing such a painful accident. The noble Angus, however, quietly replied that he had thought it was a part of the ceremony, adding that he was ready and willing to endure much more for the glory of Jesus Christ.

Thus, in less than a quarter of a century from the day St. Patrick set his foot on her emerald shores, the greater part of Ireland became Catholic. The darkness of ancient superstition every- where faded away before the celestial light of the Gospel. The groves of the pagan Druids were forsaken, and the holy sacrifice of the Mass was offered up on thousands of altars.

The annals of Christianity record not a greater triumph. It is the sublime spectacle of the peo- ple of an entire nation casting away their heathen prejudices and the cherished traditions of ages, and gladly embracing the faith of Jesus Christ, announced to them by a man who had once been a miserable captive on their hills, but now an Apostle sent to them with the plenitude of power by Pope Celestine.

Nor is it less remarkable that this glorious revolution — this happy conversion of peerless Ireland — was accomplished without the shedding of one drop of martyr blood, except, perhaps, at the baptism of Angus, when,

" The royal foot transpierced, the gushing blood

Enriched the pavement with a noble flood."

While St. Patrick was meditating as to the site he should select for his metropolitan see, he was admonished by an angel that the destined spot was Armagh. Here he fixed the seat of his primacy in the year 445. A cathedral and many other religious edifices soon crowned the Hill of Macha. The whole district was the gift of King Daire, a grandson of Eoghan.

The Apostle, having thus established the Church of Ireland on a solid basis, set out for Rome to give an account of his labors to Pope St. Leo the Great. The Holy Father confirmed whatever St. Patrick had done, appointed him his Legate, and gave him many precious gifts on his departure.

The ancient biographers give many a curious legend and quaint anecdote in relation to our great Saint. Eoghan (Eugene, or Owen) was one of the sons of King Niall of the Nine Hostages. He was a bold and powerful prince, who acquired the country called after him " Tir-Owen " (Tyrone), or Owen's country. His residence was at the famous palace of Aileach in Innishowen. [24] When Eoghan heard of St. Patrick's arrival in his dominions, he went forth to meet him, received him with every mark of honour, listened with humility to the word of God, and was baptized with all his household. But he had a temporal blessing to ask of the Apostle.

" I am not good-looking," said the converted but ambitious Eoghan; "my brother precedes me on account of my ugliness."

"What form do you desire ? " asked the Saint.

"The form of Rioc, [25] the young man who is carrying your satchel," answered the prince. St. Patrick covered them over with the same garment, the hands of each being clasped round the other. They slept thus, and afterwards awoke in the same form, with the exception of the tonsure.

"I don't like my height," said Eoghan.

"What size do you desire to be?" enquired the kind-hearted Saint.

The prince seized his sword and reached upwards.

"I should like to be this height," he said ; and all at once he grew to the wished-for stature.

The Apostle afterwards blessed Eoghan and his sons. [26]

"Which of your sons is dearest to you ? " asked St. Patrick.

"Muiredhach," [27] said the prince.

" Sovereignty from him for ever," said the Saint.

"And next to him ? " enquired St. Patrick.

"Fergus," he answered.

"Dignity from him," said the Saint.

"And after him ?" demanded the Apostle.

"Eocha Bindech," said Eoghan.

"Warriors from him," said the Saint.

"And after him? "

"They are all alike to me," replied Eoghan.

"They shall have united love," said the man of God.

"My blessing," he prayed, " on the descendants of Eoghan till the day of judgment. . . . The race of Eoghan, son of Niall, bless, O fair Bridget ! Provided they do good, government shall be from them for ever. The blessing of us both upon Eoghan, son of Niall, and on all who may be born of him, if they are obedient." [28]

St. Patrick, it is told, had a favorite goat which was so well trained that it proved very serviceable. But a sly thief fixed his evil eye on the animal, stole it, and made a feast on the remains. The loss of the goat called for investigation; and the thief, on being accused, protested with an oath that he was innocent. But little did he dream of his accuser. " The goat which was swallowed in his stomach," says Jocelin, " bleated loudly forth, and proclaimed the merit of St. Patrick." Nor did the miracle stop here; for "at the sentence of the Saint all the man's posterity were marked with the beard of a goat." [29]

About ten years before his death the venerable Apostle resigned the primacy as Archbishop of .

Armagh to his loved disciple, St. Benignus, [30] and retired to Saul, his favorite retreat, and the scene of his early triumphs. Here it was that he converted Dicho and built his first church. Here also he wrote his "Confessions," and drew up rules for the government of the Irish Church. When he felt that the sun of dear life was about to set on earth, that it might rise in brighter skies, and shine for ever, he asked to be taken to Armagh. He wished to breathe his last in the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland. But on the way an angel appeared to the blessed man, and told him to return — that he was to die at Saul. He returned, and at the age of seventy-eight, on the 17th of March, in the year 465, St. Patrick pass- ed from this world.

He was buried at Downpatrick, in the county of Down ; and in the same tomb were subsequently laid the sacred remains of St. Bridget and St. Columbkille. The shrine of the Apostle of Ireland was visited by Cambrensis in 1174, and upon it he found the following Latin inscription:

Hi tres Duno tumulo tumulantur in uno,

Brigida, Patricius, atque Columba Pius.

In Down three Saints one grave do fill,

Bridget, Patrick, and Columbkille. [31]

This illustrious Saint was a man of work, and prayer, and penance. To his last breath he ceased not to teach his people. His daily devotions were countless. It is related that he made the sign of the cross many hundred times a day. He slept little, and a stone was his pillow. He travelled on foot in his visitations till the weight of years made a carriage necessary. He accepted no gifts for himself, ever deeming it more blessed to give than to receive.

His simple dress was a white monastic habit, made from the wool of the sheep ; and his bearing, speech, and countenance were but the outward expression of his kind heart and great, beautiful soul. Force and simplicity marked his discourses. He was a perfect master of the Irish, French, and Latin languages, and had some knowledge of Greek.

He consecrated three hundred and fifty bishops, [32] erected seven hundred churches, ordained five thousand priests, and raised thirty-three persons from the dead. But it is in vain that we try to sum up the labors of the Saint by the rules of arithmetic. The wear and tear of over fourteen hundred years have tested the work of St. Patrick : and in spite of all the changes of time, and the malice of men and demons, it stands to-day greater than ever — a monument to his immortal glory. [33]

"It should ever be remembered," says the Nun of Kenmare, " that the exterior work of a saint is but a small portion of his real life, and that the success of this work is connected by a delicate chain of providences, of which the world sees little and thinks less, with this interior life. Men are ever searching for the beautiful in nature and art, but they rarely search for the beauty of a human soul, yet this beauty is immortal. Something of its radiance appears at times even to mortal sight, and men are overawed by the majesty or won by the sweetness of the saints of God; but it needs saintliness to discern sanctity, even as it needs cultivated taste to appreciate art. A thing of beauty is only a joy to those who can discern its beauty; and it needs the sight of angels to see and appreciate perfectly all the beauty of a saintly soul. Thus, while some men scorn as idle tales the miracles recorded in the Lives of the Saints, and others give scant and condescending praise to their exterior works of charity, their real life, their true nobility is hidden and unknown. God and the angels only know the trials and the triumphs of holy human souls."

[8] Lerins is an island in the Mediterranean, not far from Toulon. In 410, the very year in which St. Patrick escaped from captivity, a young noble, who preferred poverty to riches and asceticism to pleasure, made for himself a home. The island was barren, deserted, and infested by serpents — all the more reason for his choice. The barrenness soon disappeared, for labor was one of the most important duties of the monk; and it is scarcely an exaggeration to say that one-half of the marshes of Europe were re- claimed and made fruitful by these patient tillers of the soil.— Sister Cusack, Life of St. Patrick.

[11] The Slaney "rises in Loughmoney, and passes through Raholp, emptying itself into Strangford Lough, between Ringbane and Ballintogher." — Sister Cusack.

[12] "Dicho came and set his dog at the clerics. Then it was that Patrick uttered the prophetic verse, Ne trades bestis, etc.. et canis obmutuit. When Dicho saw Patrick he became gentle." — Tripartite Life of St. Patrick.

[13] Sabhall (pronounced Saul) means a barn. It afterwards became a monastery of Canons Regular. Saul is now the name of the parish.

[14] Milcho's two daughters were converted, and one of his sons was made a bishop by St. Patrick.

[15] This Laegrius (or Lear) was one of the sons of Niall of the Nine Hostages.

[16] The Hill of Tara is large, verdant, level at the top, and extremely beautiful; and though not very high, it commands extensive and most magnificent prospects over the great and fertile plains of Meath. At Tara the ancient records and chronicles of the kingdom were carefully preserved ; these records and chronicles formed the basis of the ancient history of Ireland, called the "Psalter of Tara," which was brought to complete accuracy in the third century; and from the "Psalter of Tara " and other records was compiled, in the ninth century, by Cormac MacCullenan, Archbishop of Cashel and King of Munster, the celebrated work called the " Psalter of Cashel." The triennial legislative assemblies at Tara, which were the parliaments of ancient Ireland, continued down to the middle of the sixth century; the last convention of the states at Tara being held, according to the "Annals of Tigearnach," A.D. 560, in the reign of the monarch Diarmot, who abandoned that royal palace A.D. 563. — O' Hart, Irish Pedigrees.

[17] Slane is on the left bank of the Boyne, in the county of Meath.

[18] "The Druids," writes the Abbe MacGeoghegan, " alarmed at this attempt, carried their complaints before the monarch, and said to him that, if he had not that fire immediately extinguished, he who had kindled it, and his successors, would hold for ever the sovereignty of Ireland; which prophecy has been fulfilled, in a spiritual sense." — History of Ireland.

[19] It was on this occasion that St. Patrick, when told by the Druids that the doctrine of the Trinity was absurd, as three could not exist in one, stooped down, and, pulling a shamrock, which has three leaves on one stem, replied: " To prove the reality and possibility of the existence of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, I have only to pluck up this humble plant, on which we have trodden, and convince you that truth can be attested by the simplest symbol of illustration." — Mooney.