In the following article from the Irish Ecclesiastical Record of 1891, Father James Halpin compares the 'apostle of the Irish' with the great 'apostle of the Gentiles'. I was interested to see how the writer expressed a degree of irritation with the Patrician scholarship of his day, and his perception that scholars almost seemed to be in danger of failing to see the wood for the trees. The good Father Halpin preferred not to neglect the devotional aspect for the scholarly, including, of course, the late Victorian taste for epic poetry...

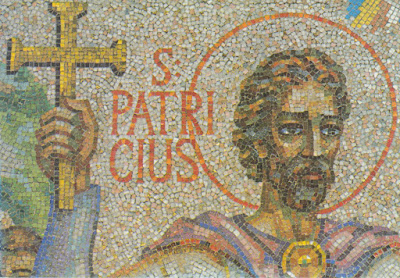

THOUGHTS ABOUT ST. PATRICK: ST. PATRICK AND ST. PAUL.

There is a strong and growing feeling that there are already too many theories about the life and labours of Ireland's national saint. It may be well, therefore, to say at the outset, that the title of this paper which may, at first view, appear somewhat startling does not imply that yet another is to be added to the number. Many are beginning to think that recent Patrician literature has concerned itself too much about a few controverted points in the life of our saint ; and too little, very much too little, about that beautiful life itself. They think that much of the theorizing on the subject might have been omitted without detriment either to the cause of historical truth or to the honour of the saint himself ; and, however ingenious or original or brilliant it may appear, they are sometimes at a loss to understand either the ground on which it rests or the good purpose it could possibly serve. In a word, there are in the saint's life, a few points which have hitherto been subjects of controversy and doubt ; with present materials they are likely, or certain, to remain so ; and it is the opinion of those to whom I refer, that it is wiser even were it not so necessary as it is candidly to acknowledge as much. And this for many reasons. Such authorities as O' Curry assure us that the materials of Irish history, to be yet written, are all but unlimited. His own researches in the field of Irish archaeology were rewarded by many valuable discoveries. The Tripartite Life, one of the seven in Colgan's Trias Thaumaturga, and perhaps the most prized of all the ancient lives of St. Patrick, was long lost, and was discovered only in comparatively recent times. Is it too much to hope for other and yet greater discoveries still in the same field ? or, may not future research decide once and for all some or all of those questions we now discuss so warmly, and upset many a theory that had cost its author much precious labour and time?

Whatever of this, we repeat that, with present materials, there are some few questions that are not likely to be solved. About the exact year of his birth, for instance, we have no less than five opinions, resting each on respectable authority. What avails it to continue the discussion, unless for the privilege or pleasure of differing from such writers as Colgan and Lanigan, Villaneuva, Jocelyn, and Tillemont. Nor does the question of place appear nearer to solution. The weight of authority seemed in favour of France ; but the balance is, perhaps, on a level since Cardinal Moran decided in favour of Scotland. And when we come to localities, there are nearly a score that claim the honour.

Again, why should it appear a matter of surprise or importance if we must leave a few such questions unanswered? A very long list, we think, might easily be made out of names the greatest in history, sacred and profane, about which similar doubts exist ; nor would St. Patrick be the only national apostle in the list. Not to go further, is it settled where St. Augustine, England's apostle, was born? Indeed, it is wonderful how little we do know sometimes of even the greatest names. Someone has undertaken to put into one sentence and it does not err in length all that is known for certain of the greatest dramatist that ever lived ; and when it comes to the question of writing or pronouncing his name an. elementary one, as would appear the learned cannot agree. In future time there maybe similar doubt about the very name of the arch-heresiarch of latter times, for the very good reason that he seems to have changed it as often as his doctrines, and to have written it himself in no less than four or five different ways. What wonder if, in the case of a saint who lived fourteen hundred years ago, we cannot determine the place of his consecration or the exact year of his birth?

And, if another reason of the same kind may be added, what we do know for certain is very much, very edifying, and worthy of our deepest attention and study. It is found in his own authentic writings. Few as they are and this is one of the strange things about him they nevertheless tell us more of his inner self than what we know of saints who wrote at much greater length.

It is a picture unique in the history of God's Church ; a beautiful picture from whatever standpoint we look at it. A great soul prepared by God for the highest mission by fitting graces and rarest gifts ; labouring with a zeal, and rewarded with a success, the like of which the world had seldom, if ever, seen equalled! Even from another and lower standpoint there is much to study and admire in the story of his life : scenes varying from the tenderest pathos to the highest drama. No wonder that such a life, with the countless legends of pathos and beauty that circle around it, should have attracted the fancy of one of Ireland's truest poets, or that the genius of Aubrey de Vere should have weaved out of such a theme a work which of itself should place his name very high among the greatest of English poets.

With those who make the lives of God's saints a study, nothing is more common as we must have observed than comparison and contrast. All have much in common ; there is, as some one has said, a family likeness between them all ; but yet a beautiful study it must be to inquire how, like star differing from star in glory, saint differs from saint in some special grace or gift that is all his own. As an example of such study, we would have quoted, did space permit, a beautiful passage in which, writing of his own St. Philip, one of his greatest sons, compares him to other saints of his time, and in a few words, worthy of so great a master of language, pointing out what he had in common with each, as well as what distinguished him from all (Newman, Idea of a University, page 235.)

But why, it may be asked, do we go back, in order to find a prototype for our saint, to the Prophets and Apostles ? The answer is, the comparison is not ours. It has been made and repeated by the biographers of St. Patrick, from St. Evin, who lived in an age so close on the saint's own, down to Fr. Morris and Dean Kinnane. It occurred to us that there must be good reason for a comparison thus frequently and authoritatively suggested, and that it would be an interesting study to seek out what the reasons were. This is the aim of the present paper : the study must be flattering to us as children of St. Patrick ; it may be edifying; it certainly has the negative merit which some recent theories can hardly claim that it can do no harm; and if the tendency, if not the effect, of some of those latter was to make people begin to doubt of the very existence of a saint, every event of whose life was the subject of endless controversy, it will have a counteracting effect, if we so far take that life and all its main events as certain, as to compare him to so great a saint, and one of so decided a personality, as the Apostle of the Gentiles.

We have said that St. Patrick's biographers generally compare him to St. Paul: one or two examples will suffice :

"A just man, indeed, was this man : with purity of nature, like the patriarchs ; a true pilgrim, like Abraham ; gentle and forgiving, like Moses ; a praiseworthy psalmist, like David ; an emulator of wisdom, like Solomon ; a chosen vessel for proclaiming truth, like the Apostle Paul ; a man full of grace and the knowledge of the Holy Ghost, like the beloved John ; a fair flower-garden to children of grace, a fruitful vine-branch . . . a lion in strength and power, a dove in gentleness and humility, a serpent in wisdom and cunning to do good ; gentle, humble, merciful to the sons of life ; dark, ungentle towards the sons of death ; a servant of labour and service of Christ ; a king in dignity and power for binding and loosening, for liberating and convicting, for killing and giving life." (Tripartite Life)

And in the hymn, of St. Sechnall or Secundinus, nephew of our saint, we find :

"Quem Deus misit ut Paulum

Ad gentes apostolum

Ut hominibus ducatum

Proeberet regno Dei"

With most of the comparisons in these passages we are not concerned now. To some of the prophets St. Patrick bore an evident resemblance notably to Moses, to whom he is often likened in the olden lives ; but this we must leave to another time, if not to another pen. Moses on the mount with God, and Patrick struggling on Cruachan; Moses before Pharao, and our saint before Laeghaire, whose heart was hardened like that of Pharao ; Moses leading the Israelites through the desert, and Patrick, on his return from captivity, obtaining food miraculously for his followers in the wilderness are pictures which we need only place side by side ; and they are only some of the points of striking, and we might almost say mysterious, resemblance between the two. The grandeur of his miracles, his familiarity with heaven, his constant intercourse with and guidance by his angel Victor, remind us rather of a theocracy than the magisterium of the Church, and suggest comparison with the saints of the Old rather than of the New Law.

The name of St. Paul is specially mentioned in both of the passages quoted, and it is with it alone we will now concern ourselves. The saints of God are distinguished one from another chiefly in this, that each seems to have what may be called a characteristic gift, a peculiar grace, a spirit which may be called his own. If, therefore, we would compare or contrast one with another, our first thought must be about the distinguishing grace of each. What was the distinguishing gift of St. Paul? Fortunately we get an answer from the distinguished writer already referred to :he treats of this very subject in two places: -

"And I think his characteristic gift is this that, as I have said, in him the fulness of divine gifts does not tend to destroy what is human in him, but to spiritualize and perfect it. According to his own words, used on another subject, but laying down, as it were, the principle on which his own character was formed ' We would not be unclothed [he says], but clothed upon ; that what is mortal may be swallowed up in life.'"

And again, in the sermon, "St. Paul's Characteristic Gifts," he says :

" To him specially was it given to preach to the world who knew the world; he subdued the heart who understood the heart. It was his sympathy that was his means of influence ; it was his affectionateness that was his title of empire." (Newman, Sermons on Various Occasions)

Readers of the life of St. Patrick need not be told that all this applies to him as literally as to his great prototype, Human sympathy, elevated by grace and spiritualized till it became a most burning zeal for souls, was also a characteristic of his. It is remarkable that of two of his most recent biographers one (Fr Morris and Dean Kinane) heads a chapter "St. Patrick's tenderness of heart," and another " St. Patrick's zeal for souls." Aubrey de Vere, in describing the saint addressing some chieftain and his court, thus beautifully touches the same trait in the conclusion of his description:

"... Gradual thus

With lessening cadence sank that great discourse,

While round him gazed Saint Patrick, now the old

Regarding, now tho young ; and flung on each

In turn his boundless heart, and gazing longed,

As only apostolic heart can long,

To help the helpless."

(Legends of St Patrick)

But the best evidence of this spirit of our saint is found in his Epistle to Coroticus, every line of which breathes the tenderest sympathy and the most ardent zeal for the souls of his people. Some of these had been carried away captive by the Welsh marauder ; from his hands they are likely to pass as slaves to the Picts and Scots ; and the saint after a first expostulation in vain sends a letter to Coroticus himself.

The tender pathos, when he speaks of his captive children, reminds us of the Epistle to Titus or Timothy or the beloved Philippians ; while the fierce denunciation of the tyrant himself vies with anything to be found in the Epistles to the Corinthians. Outside the parable of the Good Shepherd it would be hard to find a finer picture of what the good shepherd should be : -

"What shall I do, O Lord? . . . Lo ! Thy children are torn round me and plundered . . . Ravening wolves have scattered the flock of the Lord . . . Therefore I cry out with grief and sorrow : O beautiful and well-beloved brethren, whom I have brought forth in Christ in such multitudes, what shall I do for you ? I grieve, O my beloved ones ... I have abandoned my country and parents, and would give my soul unto death, if I were worthy.

Perhaps the virtue, after zeal and charity, that is most conspicuous in the two saints is humility. It may be said to be a characteristic of both, and both express it and they are constantly giving expression to it in language very similar. If St. Paul is the " last of the Apostles," a "persecutor of the Church," "carnal," and "sold under sin," St. Patrick is " a sinner," and " the unlearned," "the rudest and least of all the faithful," and was brought "captive to Ireland, as we deserved, for we had forsaken God."

If the spirit of the two saints be so similar, if their characteristic gifts be identical, we should expect that the resemblance should show itself (2) in the style of their writings and (3) in the method of their missionary labours. And so, we think, it is. Like everything about St. Patrick, his style is marked by a strong distinctive personality ; so much so, indeed, that some one has said it is inimitable. It is, according to an ancient writer, its own witness ; yet we are constantly met with passages in both the Confession and Epistle which remind us of St. Paul's Epistles, in phrase and style, as well as in sentiment. True, an explanation may be found in St. Patrick's thorough acquaintance with Sacred Scripture. That he studied in the most famous centres of learning and sanctity, and that Sacred Scripture formed part of his course, are equally certain. The Tripartite mentions his visit to St. Martin at Marmonties ; Probus assures us that he spent many years with St. Germanus at Auxerre ; and another writer assures us that he studied Scripture at Borne. Wherever he studied it, there can be no doubt of his remarkable familiarity with it ; his frequent quotations, and still more his constant allusions, bear ample testimony to a knowledge of every part of Scripture that was simply wonderful. This may explain any similarity in style, as well as in ideas, of the kind referred to; but we think it would be as satisfactory and, perhaps, more reasonable to say that, as the two great souls were similarly gifted by God, so, when they came to speak, their thoughts clothed themselves in like words and phrases.

The same principle would explain the similarity that is said to exist between passages of the Lorica and St. Francis Hymn to the Sun; for among more modern saints there is none to whom our national apostle can be better likened than the seraphic Francis; a fact which we may say in passing may go some way to account for the mutual attachment and devotion of their children to this day. Without making any attempt at collating, which would be unnecessary for those who are familiar with St. Paul's style, it will be sufficient to quote one or two passages from writings with which we are, perhaps, less familiar. Does not the following remind us of a conclusion of some of St. Paul's Epistles ?

" In that day we shall arise in the brightness of the sun, that is, in the glory of Jesus Christ, and all redeemed we shall be, as it were, the sons of God, and co-heirs of Christ, and made like to His image in the future. For from Him,and in Him, and by Him are all things ; to Him be glory for ever. Amen." (St Patrick's Confession)

In another part of the same we find and it shall be our last quotation :

" And on another night, whether in me or near me, God knows, I heard eloquent words, which I could not understand until the end of the speech, when it was said : ' He who gave His life for thee is He who speaks in thee,' and so I awoke full of joy. And, again, I saw one praying within me; and I was as it were within my body, and I heard, that is, above the inner man, and there he prayed earnestly with groans . . . and I awoke, and remembered that the Apostle said : ' Likewise the Spirit also helpeth our infirmity.'" (Rom. viii. 26.)

In fine, a word on the method of their labours. Both became all things to all men, and in a very special manner. The method of St. Patrick was not that of sweeping change or general revolution : the very opposite is particularly noted. He adapted and perfected rather than rejected. The laws he found before him he sought to purify, rejecting only what may not be retained. Witness his taking part in the compilation of the Senchus Mor in A.D. 439 :

" I to that people all things made myself,

For Christ's sake, building still that good they lacked,

On good already theirs". (Aubrey de Vere, Legends of St Patrick)

Even whatever knowledge of art and handicraft he found he carefully used for the glory of God, and the purposes of his mission. The same author, in a poem entitled St. Patrick's Journey to Armagh, describes his usual following ; and, after mentioning Benignus his psalmist, Lecknall bishop, Ere his brehon, Mochta his priest, he adds :

". . . And Sinnell of the bells,

Eodan his shepherd, Essa, Bite, and Tassach,

Workers of might, in iron and in stone,

God taught to build the churches of the faith

With wisdom, and with heart-delighting craft."

How like is all this to the spirit and method of him who became all things to all men, and who while he was "the special preacher of divine grace is also the special friend and intimate of human nature," who would circumcise the beloved Timothy to please the Jews, and who would himself conform to the rite of the Nazarites for the same purpose!

Again, it is pointed out by writers on St. Patrick and, indeed, we cannot fail to remark it that he, as if instinctively, first sought the enemy in his "centre and citadel" Royal Tara, Ailech of the Kings, Cruachan, and Cashel; such seemed to be the goals to which he would first direct his steps ; and if he turned aside at all it was to seek out the stronghold of another and more powerful enemy, that of idolatry ; for one of his first visits was to Magh Slecht to destroy the great idol Crom Cruach. In like manner do we find his great prototype in the great centres not of a nation only, but of the world in Athens and Corinth, in Jerusalem and Rome. St. Patrick, boldly preaching the Gospel before council of king and brehon and druid, seems but a counterpart of St. Paul, proclaiming the name of Christ to the Jews in their synagogues, and to Gentiles in the very Areopagus.

There are many other points of resemblance of a minor kind, which we can only mention in a few words. Their mission was the same: St. Paul preached to the Gentiles; St. Patrick to "a barbarous nation." In both cases there was a vocation direct from heaven ; its manner was like in each case, for the description of the scene in which St. Patrick heard a voice he knew not whether "within him or close by," and in which "fell scales from mine inner eyes," remind us, surely, of the great event that happened on the way to Damascus. St. Paul only knew Christ and Him crucified; St. Patrick Tillemont tells us was learned only in Scripture and sacred science. Both stand out unlike to, and distinct from, all around them, by a strong and peculiar personal character. In fine,when we hear of "the unearthly elevation" of his (St. Patrick's) character; that his character had a decided, though human share in his work ; that he " subdued rather than persuaded," and that the "peculiar character of his apostolate came from the conviction of a special message from God," we cannot but feel that all this applies equally to the great Apostle of the Gentiles.

We have stated that the comparison we have been thus far considering is suggested by all the biographers of our saint. The beautiful life by our distinguished countryman, Aubrey de Vere for, indeed, his series of poems may be said to be a life is no exception ; and, as we have quoted from him so often, we may fitly conclude by a passage in which he refers to it :

". . . The words that Patrick spake

Were words of power. Not futile did they fall ;

But, probing, healed a sorrowing people's wound.

Bound him they stood, as oft in Grecian days

Some haughty city sieged, her penitent sons

Thronging green Pnyx or templed Forum hushed,

Stood listening to that people's one true voice,

The man that ne'er had flattered, ne'er deceived,

Nursed no false hope."

JAMES HALPIN, C.C.